Most Sicily enthusiasts and even historians of Islamic history would not be at fault for having to re-read the title of this article. The “Palermo Qur’an” has been called the “single most important artifact so far known to survive from Muslim Sicily.”1 Indeed, it is a window into the religious, cultural, and political history of Muslim Sicily. Despite its significance, there is limited research on this unparalleled relic and few sources other than Jeremy Johns‘ “The Palermo Qurʾān (AH373/982–3AD) and Its Historical Context.” While much will be left to the reader’s imagination, I have tried to present an accessible summary of what we know in this brief post.

The Palermo Qur’an was copied by hand in 982–3 CE (372 in the Islamic calendar), while Sicily was ruled by the Kalbid dynasty during the Fatimid caliphate. It was copied at a time when Palermo was one of the great capitals of the Islamic world, boasting up to 300 mosques .2

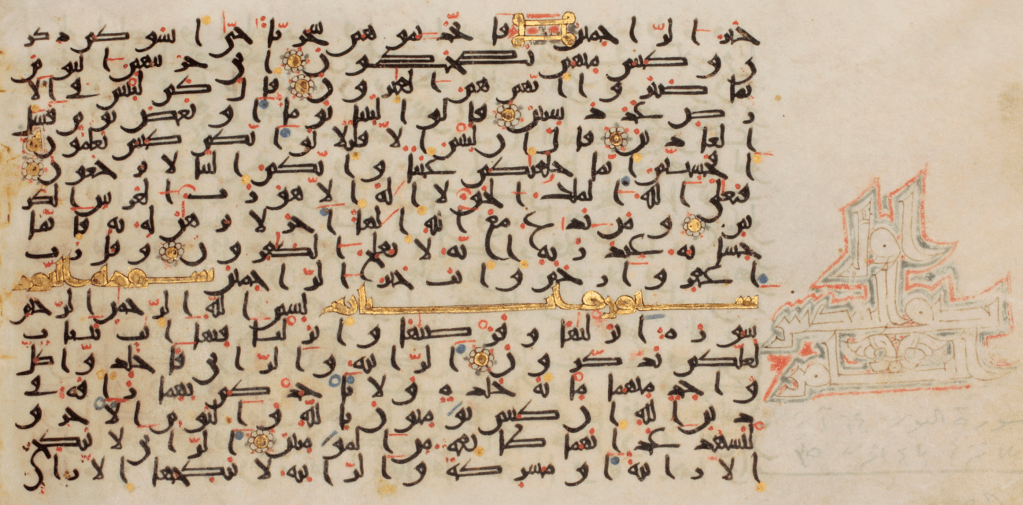

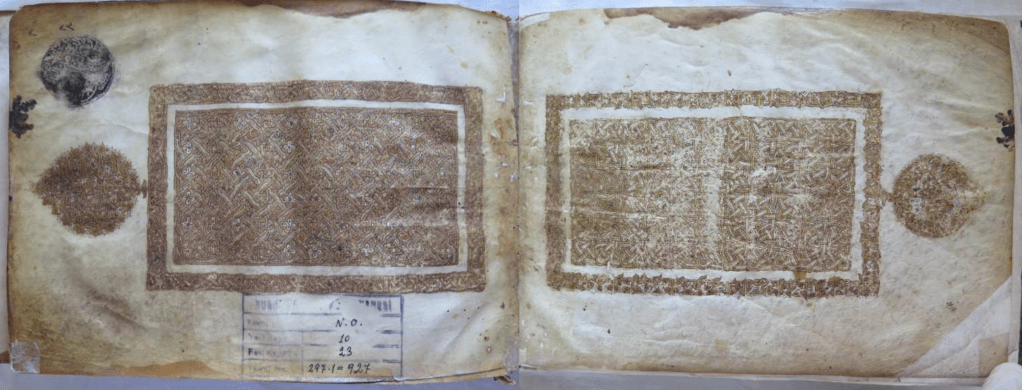

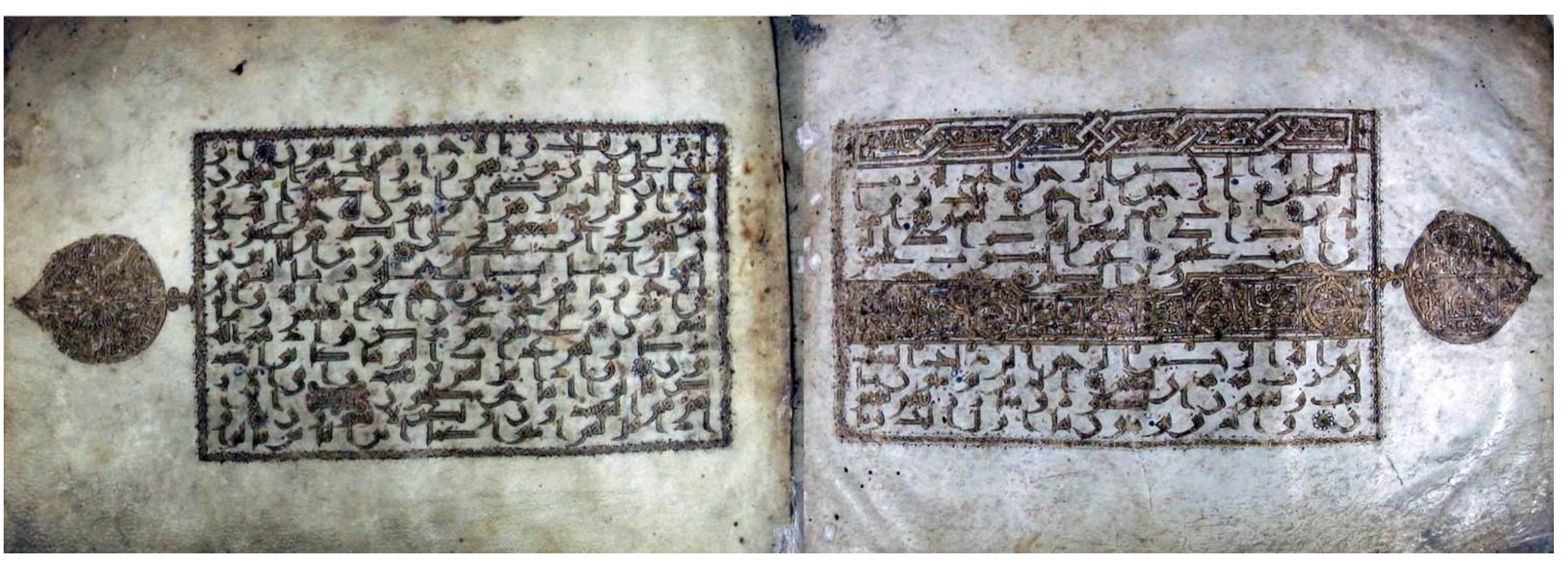

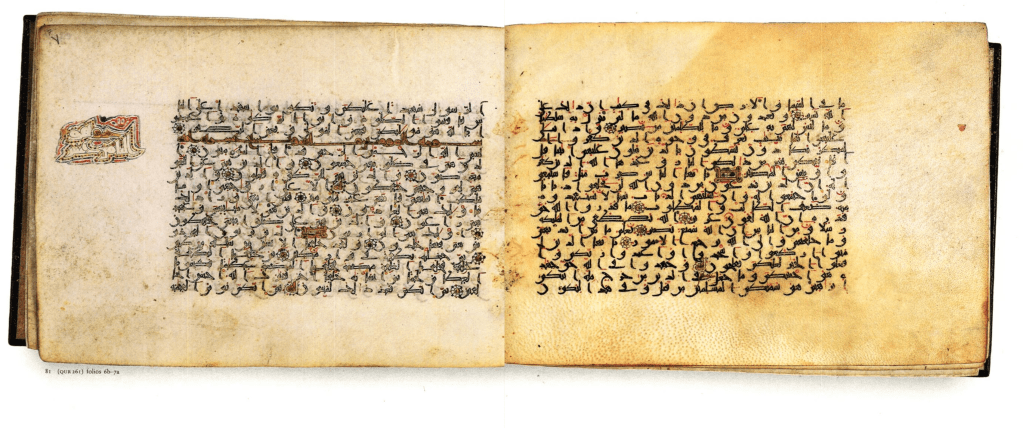

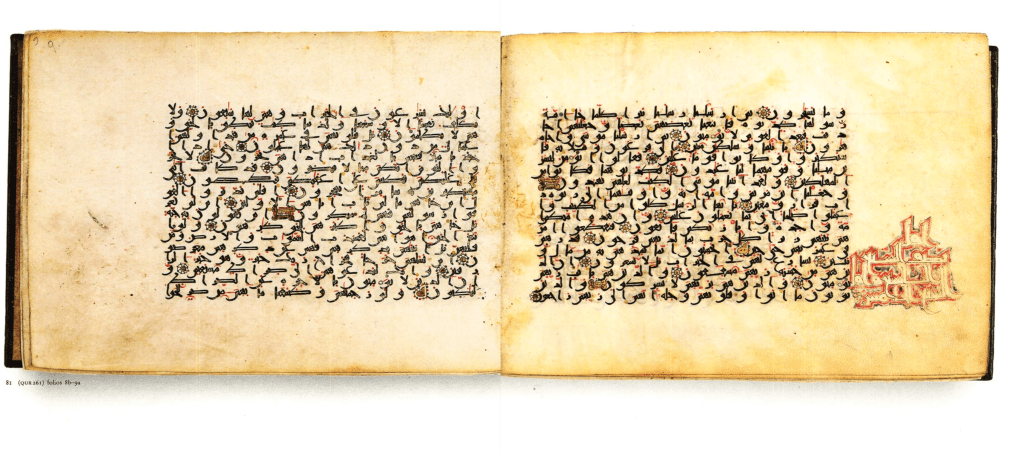

Bifolio from the Palermo Qur’an. Copyright: Istanbul, Nuruosmaniye Kütüphanesi

Bifolio from the Palermo Qur’an. Copyright: Istanbul, Nuruosmaniye Kütüphanesi

Today, most of the Palermo Qur’an is preserved at the Nuruosmaniye Library in Istanbul. Four of the original twenty-nine quires (sheets of parchment that folded to form pages) have been separated from the manuscript. Two quires, which each contain five double-sided pages, are in the possession of the privately-owned Khalili Collection of Islamic Art. The whereabouts of the remaining two quires are unfortunately unknown. While the manuscript is therefore only semi-complete, it is the most complete surviving Qur’an known to have survived from Muslim Sicily. To date, the only other confirmed Sicilian Qur’anic manuscript that I am aware of is a single page, which was repurposed as a cover of a marriage registry in 1542 and found in a church library in 20103.

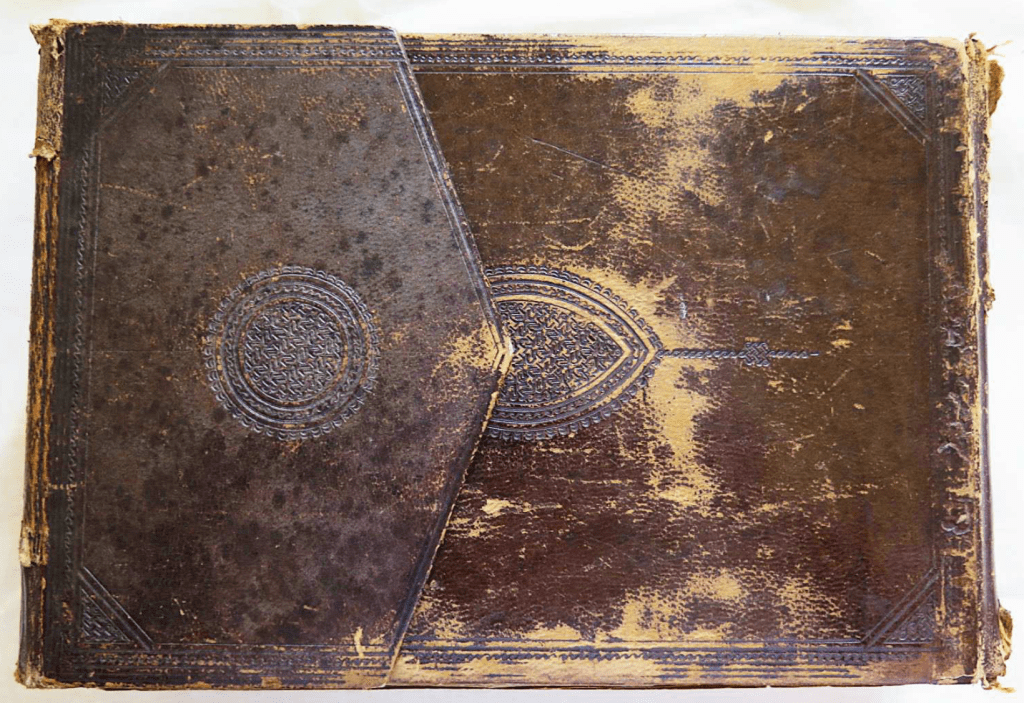

The calligrapher who copied the Qur’an took great care to meticulously pen 17 lines of text on each page with clarity and elaborate style. The manuscript is in the oblong (wide book vs. a tall book) shape, which was archaic for its time.4 François Déroche describes the text itself as “New Style” Kufic script, defined by breaks and angular forms and by extreme contrasts between the thick and thin strokes. The manuscript is written on sheepskin parchment instead of paper, a reflection Déroche claims, of the “conservatism of the Western Islamic World.”5 It is estimated that at least 70 sheep would have been needed to make this manuscript.6 Given its elegant presentation, Johns suggests, the manuscript was, “not for just private consumption, and it was the patron’s intention that it be seen and admired by others.”7

A Rebellious Profession of Faith

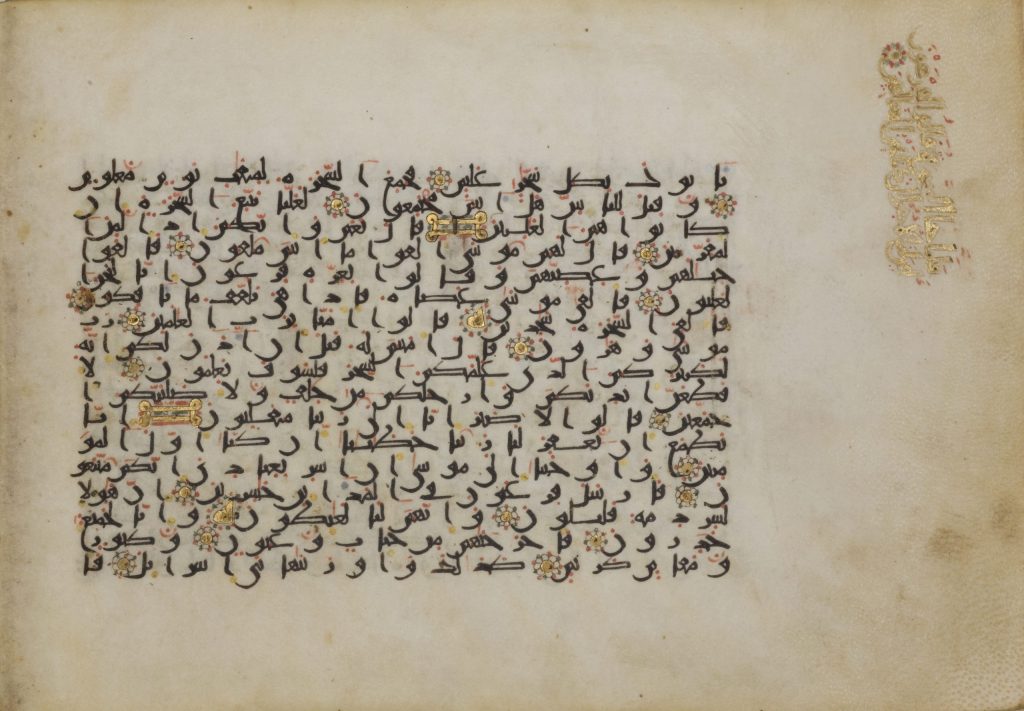

The Palermo Qur’an opens to an elegant vignette (pictured below) with a controversial profession of faith written in gold, outlined in black, with blue and red dots in the voids between letters.

Detail of the vignette. Copyright: Istanbul, Nuruosmaniye Kütüphanesi

The text in the vignette reads, “There is no god except God, Muḥammad is the Messenger of God, The Qurʾan is the Speech of God, and is not created.”8

The last part of this statement about the uncreated nature of the Qur’an would have been a controversial belief in 982 under the Kalbid rulers of Sicily who were appointed by the Fatimid caliphate. The Fatimids believed the Qur’an was created over time and that its words had been composed and edited by their ancestor the Prophet Muhammad. The people of Sicily however followed the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence and therefore believed that the Qur’an was “the speech of God” and it was not created. As Johns points out, after the victory of the Fatimid caliphate, the question of the created-ness of the Qurʾan was a source of religious and political conflict between the leaders of the Fatimids and indigenous Maliki scholars in Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and western Libya). This conflict even led to a violent sectarian conflict in Baghdad and across Ifriqiya.9 Incidentally, it would seem the controversy also made its way to Sicily. The Palermo Qur’an therefore contains a dogmatic profession about the nature of the Qur’an that was as much a statement of political opposition as it was a religious belief.

The Patron of the Palermo Qur’an

Without the name of the patron, we can only speculate about the Sicilian Muslim who commissioned the Palermo Qur’an. Johns suggests that he is likely to have been a Palermitan of distinguished family. Perhaps he had his own disciples and so therefore was a prominent scholar and teacher. He may have commissioned the Qur’an for use in his own mosque. The quality of the manuscript, the use of wide margins, and elegant design suggest that he was a man of significant wealth.

Given the profession of the Qur’an’s non-createdness, he is unlikely to have been connected to the Kalbid rulers of Sicily. The Kalbids, which at this time were a vassal of the Fatimid emirate and would not have wished to be associated with such an openly anti-Fatimid profession of faith. The patron of the Palermo Qur’an was therefore rebelliously proclaiming not only his adherence to the Maliki community in Sicily but also his opposition to any ruler who was of the other three schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence.

How the Palermo Qur’an came to Istanbul remains unanswered and leaves room for imagination. Like the four Sicilian documents found amongst the “Damascus Documents,” which are today in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, the Qur’an could have been brought into the Ottoman Empire by immigrants from Sicily, or refugees following the Norman invasion in the 1070s, or even by Muslims escaping the Spanish Inquisition. Perhaps confirming the legitimacy of this final possibility, Johns observes, the first and last pages of the Palermo Qur’an bear the stamp of Sultan Bayezid II. The Sultan, who ruled from 1481–1512 is remembered for welcoming Muslims and Jewish refugees and giving them citizenship in the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion from Spanish-controlled lands in 1492.10 Until scholars confirm the story of the Palermo Qur’an’s journey to Istanbul, I prefer to imagine this possibility–its journey east was the result of an act of welcoming refugees into safety.

The Palermo Qur’an is a beautiful and unique reminder of Sicily’s rich religious and cultural history. At a time when the president of Italy openly proclaims that “there is no place for Islamic culture in Europe” and that it is “incompatible,” knowledge of Sicily’s history is more important than ever.

Sources:

- Johns, Jeremy. “‘The Palermo Qurʾān (AH373/982–3AD) and Its Historical Context’ (Final Pre-Print Version: Now Published).” in The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa, edited by Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick & Mariam Rosser Owen, Leiden and Boston : Brill, 2017 Chapter 29, pp. 587–610. (2017): 587–610. Print. P. 10. ↩︎

- Granara, William, and ﺟﺮﺍﻧﺎﺭﺍﻭﻟﻴﻢ. “Ibn Hawqal in Sicily / ﺍﺑﻦ ﺣﻮﻗﻞ ﻓﻲ ﺻﻘﻠﻴﺔ.” Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 3, 1983, pp. 94–99. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/521658. Accessed 22 Jan. 2024. p. 96. ↩︎

- Marijn van Putten, a Historical Linguist, has speculated that an ancient Qur’an in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France could have originated in Sicily given its similarities to the unique calligraphy in the Palermo Qur’an. ↩︎

- George, Alain. “Coloured Dots and the Question of Regional Origins in Early Qur’ans (Part II) / الملونة النقاط وقضية أصول الإقليمي في المصاحف المبكرة (الجزء الثاني).” Journal of Qur’anic Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, 2015, pp. 75–102. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44031112. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024. P.77 ↩︎

- Déroche, François. The Abbasid Tradition: Qur’ans of the 8th to the 10th Centuries AD. Nour Foundation in Association with Azmimuth and Oxford University Press, 1992. Print. P. 146.

↩︎ - Johns, 12. ↩︎

- Johns, 24. ↩︎

- Johns, 15. ↩︎

- Johns. 16 ↩︎